Author: Cedric Welt

We’ve all been there: enjoying a nice time out with friends or family when, as usual, someone decides to light up a cigarette. Depending on the country you’re in and the rules in place, this person may even be lighting up in an indoor environment like a restaurant or bar. At this moment a few thoughts pop in your head: this smells, and probably more importantly is this smoke killing me? Well, you’re in luck! This blog post will answer the second question and a few other questions you may have on tobacco smoke. In the following paragraphs, we will go in depth into the origins, composition and consequences of environmental tobacco smoke.

To begin, let’s define tobacco smoke. Tobacco smoke is composed of two elements: “active” smoke, and “passive”, or environmental, smoke. The second type is also referred to as second-hand smoke. Active smoke is what is inhaled by the smoker and never gets released in the air. This smoke is a major health hazard for the smoker themselves as it enters their lungs and body. Passive smoke is composed of “mainstream” smoke that is exhaled by the smoker, and “side stream” smoke that is passively released by the cigarette without going through the filter. Sidestream smoke is what you see coming out of a lit cigarette on an ashtray or in the smokers’ hands. Both types of smoke are called environmental tobacco smoke, which will be abbreviated as ETS from now on. ETS is created by combustion of tobacco products like cigarettes, cigars, pipes, etc…

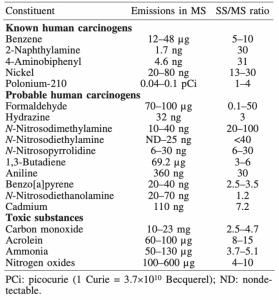

ETS and its two subtypes, mainstream and side stream smoke, are composed of over 4000 different compounds and chemicals. The following table provides a shortened list of some of the compounds that are present in ETS in unfiltered cigarettes:

Table 1: Emissions of selected tobacco smoke constituents in fresh, undiluted mainstream smoke (MS) and diluted sidestream smoke (SS) from unfiltered cigarettes according to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) report

(Source: Jaakkola & Jaakkola, 1997)

As we can see, all the substances above are at the very least toxic, and at most known human carcinogens. First, we observe the presence of benzene, a highly carcinogenic substance also found in car exhaust and is a major contributor of smog in urban areas. We can also notice the presence of ammonia and formaldehyde, substances found in certain consumer products and furniture. Most of these compounds have a larger SS/MS ratio, meaning they are found more frequently in sidestream smoke compared to mainstream smoke. In all cases, these compounds are detrimental to human health. A less complex image of some these compounds and elsewhere we can find them is shown below:

Image 1: Common toxins found in ETS

Image 1: Common toxins found in ETS

(Source: CDC)

Now that we have defined ETS, it is important to know where it is most commonly found: inside homes, cars and, in many countries, restaurants and bars. ETS is known to linger due to its complex mixture of particulate and gaseous matter. In general, mainstream smoke (directly inhaled then exhaled by the smoker) is in a gaseous (vapour) phase which, due to a higher burn temperature, presents slightly less carcinogenic compounds than sidestream smoke which is in a particulate phase. This is much more harmful to the people in the vicinity of the smoker and is thus a much more harmful type of secondhand smoke. As well, sidestream smoke is more likely to attach itself to fabric and textiles inside the home or on one’s clothes. This is one reason smokers’ clothes, cars and furniture frequently smell of smoke even without a lit cigarette nearby. The following image taken from a report by The Truth Initiative, the United States’ largest anti-tobacco nonprofit group, outlines the health effects that smoke, and particularly sidestream smoke (ETS) has on human (and animal!) health and indoor air quality:

Image 2: Poster outlining health and societal effects of second-hand smoke

(Source: Truth Initiative)

As the poster (and the full report linked at the end of this post) shows, ETS presents grave dangers to human health and overall indoor air quality. The presence of smoke-free laws is a major contributor to reducing exposure to ETS as it is one of the only ways to ensure this smoke does not enter or remain in indoor spaces. Even with advanced ventilation systems, the toxicity and ability of smoke to remain attached to surfaces and fabrics ensures that the room will conserve tobacco odours and present less than ideal air quality for days, weeks or even months on end. It is for these reasons that the best way to ensure proper indoor air quality with regards to tobacco is to simply ban smoking in all indoor public spaces. No amount of ventilation will ever replace the advantages of not exposing the space and occupants inside from this smoke in the first place.

To conclude, we have seen what tobacco smoke is made of and what the major differences between primary and second-hand smoke (ETS) are. We have then outlined the major toxic elements present in this smoke and the impact that all these compounds have on the human body and indoor environments. The impact of smoke on air quality is immense and should be treated as a true public health issue. And yet, we already know of a simple yet paramount solution to dealing with ETS: outlawing its presence indoors in the first place! This move not only allows all occupants to enjoy cleaner air, but also preserves their short term and long-term health. Hopefully you will now be able to show this post to that one smoker you know and maybe, just maybe, they’ll choose to light up outside instead…

References

[1] Jaakola, M., & Jaakkola, J. (1997). Assessment of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. European Respiratory Journal, 10, 2384-2397.

[2] Law, M. R., & Hackshaw, A. K. (1996). Environmental tobacco smoke. British Medical Bulletin, 52(1), 22-34.

[3] Truth Initiative. (April 2018). Secondhand Smoke. Washington, DC: Truth Initiative. Accessed at: https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/harmful-effects-tobacco/secondhand-smoke

[4] WHO Regional Office of Europe. (2000). Air Quality Guidelines – Second Edition . Chapter 8.1 Environmental Tobacco Smoke. Copenhagen, Denmark.

[5] Secondhand Smoke. Wikipedia.com

[6] Tobacco Smoke. Wikipedia.com

[7] CDC.gov

[8] Health Canada Website: Tobacco. Accessed at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-concerns/tobacco.html

[9] American Cancer Society: Secondhand Smoke. Accessed at: https://www.cancer.org/healthy/stay-away-from-tobacco/health-risks-of-tobacco/secondhand-smoke.html